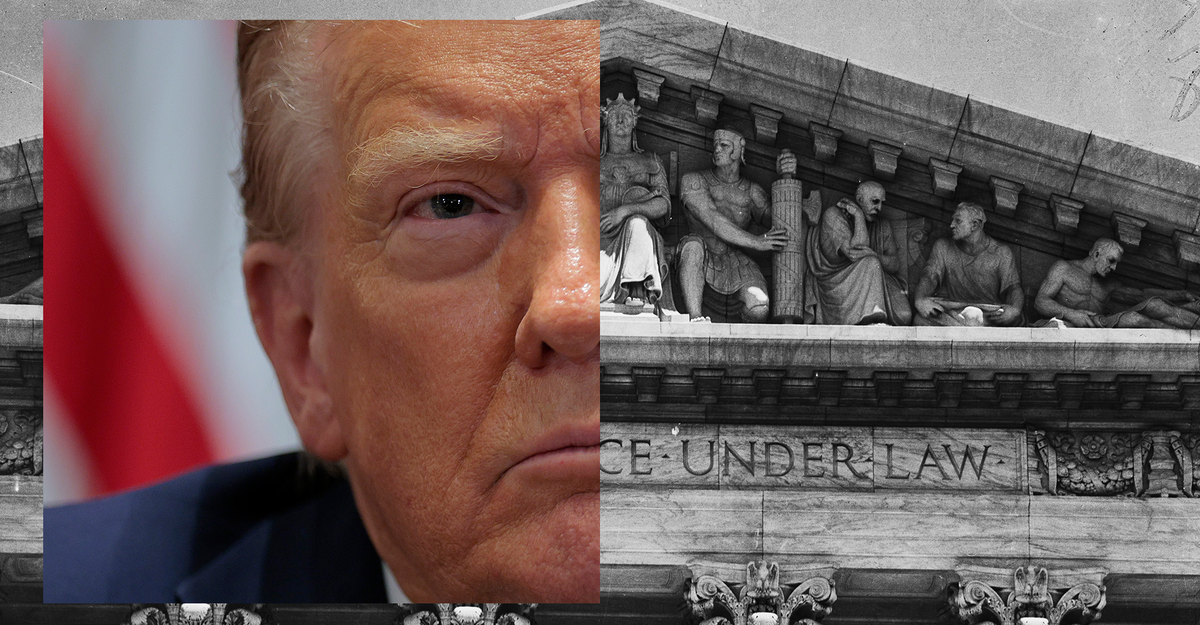

In lawsuit after lawsuit, President Donald Trump’s opponents have contested his claims of authority. To a very real degree, lower courts have been willing to step in and say no to Trumpian excess. The Supreme Court, by contrast, has demonstrated far more openness to letting Trump have his way.

That dynamic—lower-court intervention followed by more deferential Supreme Court review—will soon face its most important test. Just before Labor Day weekend, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued a decision (V.O.S. Selections v. Trump) invalidating most of Trump’s claimed authority to impose tariffs unilaterally. Trump has already appealed the decision, and the matter will be resolved by the Supreme Court sometime soon. What that Court decides will be crucial, both for the narrow (though immensely important) question of tariff imposition and for the far broader and even more significant question of presidential authority generally.

If the Court says that Trump has overstepped, it will be the first substantive instance of the justices intervening to restrain him. But if the Court defers to Trump’s declaration of an emergency, it will be an enormously consequential decision, signaling the Court’s complete abdication of review authority. To say that the future of the constitutional system of checks and balances hinges on what the Court does is no exaggeration.

In the tariffs case, Trump’s underlying claim is that he has the power to impose them unilaterally because of a supposed national economic emergency. Trump has run this play before, using false declarations of emergency conditions to justify his claims of extraordinary emergency powers. Under this guise, Trump has asserted authority to combat an immigration “invasion” and to take over policing in the District of Columbia. The tariff case will reveal whether the Court will give any scrutiny to emergency declarations and the immense powers they can bring.

[Listen: Trump’s tariff disaster]

At issue in the case is a statute known as the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which grants the president certain emergency authorities “to deal with any unusual or extraordinary threat” to the American economy from abroad. The IEEPA gives the president wide-ranging economic powers to “block” transactions, for example, or to “regulate” or “prohibit” importation of foreign goods if the president thinks it necessary. Powerful stuff indeed, but, notably, the statute does not use tariffs, duties, or any similar terms—customs or taxes or imposts—in describing the president’s powers.

What some might see as a cautious, narrow authority to deal with truly urgent problems, Trump sees as a loophole through which he can drive a giant truck. Early in his second term, Trump declared a national emergency based on the trafficking of opioids into the United States and the alleged failure of Mexico, Canada, and China to address those threats.

Calling this circumstance an unusual and extraordinary threat, Trump then invoked his IEEPA powers and imposed tariffs of up to 25 percent on Chinese, Mexican, and Canadian goods. He argued that even though tariffs were not explicitly authorized by the statute, they were fairly encompassed in his authority to regulate the importation of goods or block them altogether.

Then, in April, on what he called “Liberation Day,” Trump again invoked his claimed authority under the IEEPA. This time, the national emergency was the “lack of reciprocity in our bilateral trade relationships, disparate tariff rates and non-tariff barriers.” Based on perceived inequities, Trump imposed country-specific duties on the products of numerous countries, with rates as high as 50 percent.

In May, a unanimous three-judge panel of the Court of International Trade struck down Trump’s tariffs. The court looked at the substance of Trump’s claims and said that the “IEEPA requires more than just the fact of a presidential finding or declaration” because “it does not grant IEEPA authority to the President simply when he ‘finds’ or ‘determines’ that an unusual and extraordinary threat exists.” In colloquial terms, the court threw a red flag on the fake emergency.

[David Frum: How Trump gets his way]

Just last week, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit reviewed that decision and reached the same result, albeit on different grounds. The circuit court rejected Trump’s claim of tariff authority, with the seven-judge majority concluding that the IEEPA does not explicitly authorize the tariffs that Trump attempted to impose. In focusing on and rejecting Trump’s statutory IEEPA authority, the majority avoided ruling on the merits of Trump’s underlying emergency declarations.

Not so for the four dissenters (two Bush appointees and two Obama appointees). They acknowledged that presidential determinations of an emergency are reviewable, but noted that earlier decisions by the Supreme Court meant that the review was “very tightly limited.” The dissenters determined that they would not look behind Trump’s claim that the trade deficit had worsened to such a degree that it had become a national emergency. In short, they accepted at face value Trump’s claim that:

Large and persistent annual U.S. goods trade deficits have led to the hollowing out of our manufacturing base; inhibited our ability to scale advanced domestic manufacturing capacity; undermined critical supply chains; and rendered our defense-industrial base dependent on foreign adversaries.

And there you have it: At least four jurists are willing to say that simply by the ipse dixit of saying there was an emergency, the president can create one—even in a case where the so-called emergency has persisted for years.

If that is the case, then the president’s control of the national economy by emergency declaration becomes near plenary. Economic claims are especially strong given the fungible nature of economic production. For example, in defending Trump’s tariffs before the federal circuit, the government attorneys went so far as to say that the onlylimit on the president’s emergency economic authority was that he had to find that the emergency had a source that was in substantial part outside the United States. Thus, in Trump’s view (a view apparently accepted by the four dissenters), the president could declare that the persistent budget deficit had grown so large as to become a national economic emergency. He could then make a factual finding that a part of the cause of the deficit was the lack of taxes paid on imports, and on that basis raise taxes. Looked at through this prism, the claimed authority at issue in the tariff cases is truly extraordinary—and the damage that its validation could do is more extraordinary yet.

From The Atlantic via this RSS feed

The Supreme Court: fails literally every test in recent history